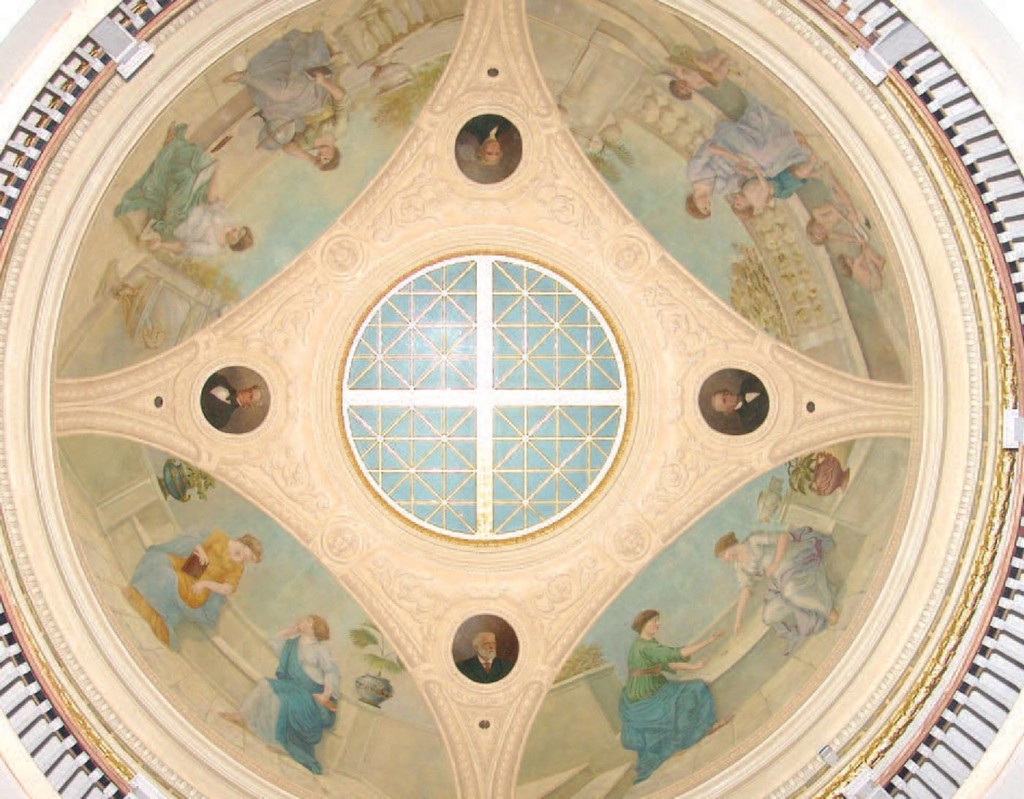

Eugene B. Monfalcone’s paintings in the dome of the Rotunda of Ruffner Hall depict the foundations of learning.

In times of transition, I tend to turn to the stars. So the year I came to Longwood, I visited an astrologist. “Learn to be rooted but strive to be free,” she advised. “Be prudent, be practical — but soar.”

This fall, with the same mix of caution and idealism once counseled by Madame Fraya, our university celebrates the confluence of two auspicious transitions: the arrival of its energetic new president and the 175th Anniversary of its founding. To celebrate such good fortune, the Longwood community will naturally spend some time honoring our intellectual roots, reveling in our many successes and dreaming of what lies ahead. With a promising new leader and a long, fruitful history, there’s a lot of reveling to do and a lot of lucky stars to thank.

Any sober assessment of Longwood’s past, present and future necessarily begins with an appreciation for the value of the education offered here—an education steeped in the richness of history, philosophy and music, as well as art, drama, literature and foreign languages. Grouped together, these disciplines make up the humanities — academic areas of inquiry that scrutinize human culture, develop analytical thinking and encourage creative thought.

For 175 years, these programs of study have fashioned the commonwealth’s students into resourceful citizen leaders: deep thinkers and active members of the community who confront the challenges of the world with confidence and ingenuity. To rejoice in the history of the university is to rejoice in the value of the humanities.

In an increasingly commercialized environment that often understands higher education primarily in vocational terms, courses in philosophy, art or world literature are sometimes seen, at best, as marginally beneficial adventures to be paired with more practical, career-oriented courses. At worst, they are deemed extravagant and ultimately irrelevant detours that squander public funds. College students nationwide who specialize in the humanities, moreover, are occasionally stereotyped as hopelessly impractical, almost as if they plan to spend four years learning to hang glide. In learning to soar, the argument goes, students in the humanities neglect to be grounded. Or gainfully employed.

Such arguments fail to recognize how vital the humanities truly are to achieving everything a university education should make possible for our students, both as professionals and as human beings. A foundation in ethics, history, languages and the arts is what makes success in more specialized areas possible.

Both parts of Madame Fraya’s advice hold true: The humanities keep us rooted even as they allow us to be free. Because they support the foundations of an educated mind, they are utterly and ineluctably practical.

The accountant who serves diverse populations, the special education teacher who writes a grant proposal, the pharmacist who under- stands the health-related impacts of the historical tensions in her neighborhood — all profit from their undergraduate training in the humanities in a useful, realistic way. What’s more, when the accountant changes careers, when the teacher is promoted to principal, when the pharmacist buys her own drug store, these graduates will lean on the practical skills they developed in their humanities courses at Longwood — skills in writing, analysis, interpretation, communication and innovation.

If the Longwood experience can be summarized as a mix of both caution and idealism, the sensible, cautious, ambitious student will choose the humanities every time. In this year of transition, the university will return to its roots by commemorating— through a yearlong series of speakers, recitals, exhibitions and student/faculty panels — the foundational role the humanities have played in the remarkable history of the university. Beginning in early September and culminating in March, when Longwood hosts the Virginia Humanities Conference for the first time, “Humans Being” will explore the vitality of the humanities and their importance to the achievements of our students and alumni. Practically speaking, there may be no better way to celebrate the enduring legacy of the Longwood experience.

Wade Edwards is an associate professor of French in the Cook-Cole College of Arts and Sciences and chair of the Department of English and Modern Languages.

The 16th-century French humanist Michel de Montaigne, an ancestor of sorts to Madame Fraya, once wrote that “there is no knowledge so hard to acquire as the knowledge of how to live this life well.” As I reflect on all that our institution has become in 175 years, I think Montaigne would have been delighted to see what’s been accomplished at Longwood University, where generations of students have learned to live well by embracing an education that is at once practical, inspired and intrepid.

By: Wade Edwards