The Gateway Arch, that gleaming symbol of westward expansion, of America’s progress and promise, stands on one bank of the Mississippi River in St. Louis. The other bank might as well be a world away.

Across the river lies East St. Louis, Ill., where poverty is ubiquitous, opportunity scant and crime rampant.

If you drive over the Poplar Street bridge—four lanes of asphalt to a place most people would rather avoid—one of the first things you’ll see is a crumbling concrete building overrun with weeds and scrub brush.

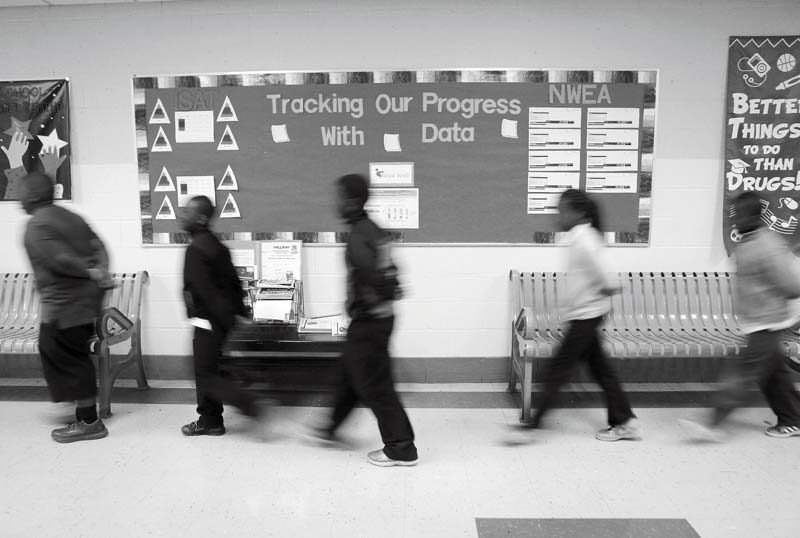

And if you stand in the middle of State Street, in front of East St. Louis Senior High School, and look west, you can see the famous arch seemingly rising out of the road on the horizon. For the students inside the school, however, a way out is elusive. Progress is a dream.

The situation, on its surface, seems hopeless.

East St. Louis students are faced with an avalanche of reasons they can’t succeed: annual test scores among the lowest in the state, more than half of students living below the poverty line, median household income around $22,000. Eighty-two percent of the children depend on food stamps to live, and almost a third of the city’s births are to teen mothers. There is no garbage collection—most trash is burned or dumped in vacant lots.

“It’s only hopeless when you look at the statistics and not into the eyes of the kids,” said Dr. Chris Jones, associate professor of education. “These kids want to learn—they want to improve their dire situation, and so do their principals and teachers.”

For Jones ’93, M.S. ’94, it’s a situation that needs urgent attention. Four years ago, he partnered with JP Associates, a company specializing in improving school performance, on a five-year federal school leadership grant to implement an innovative program to recruit, train and mentor administrators in East St. Louis schools. Jones has been associated with JP Associates for the past decade, working with them on an initiative to combine expertise and resources to effect positive change.

Dr. Chris Jones ’93, M.S. ’94 (second from left), works with East St. Louis school administrators Wanetta Jones (left), Lori Chalmers and Tina Frye to help them build the skills they need to help their schools be successful.

The problems endemic to East St. Louis are problems that Jones can’t change: not the poverty, not the crime, not even the test scores. Various groups have tried for decades to sweep in with solutions from the outside, and all have largely fallen short. “This effort is about changing from within,” said Jones. “It’s about giving school administrators tools they can use to effect change in the schools themselves. I can’t do it for them: They have to do the heavy lifting themselves.”

The grant established three yearly leadership academies—intensive training sessions in which Jones and Doug Blancero from JP Associates teach critical leadership skills to the district’s principals and assistant principals. For the first few years, we were building the necessary skills for success,” said Ethel Shanklin, a former East St. Louis principal and project liaison. “The administrators now have the tools; proper and consistent application will be the keys to the success of the process.”

Then, each month, Jones and his colleagues travel back to East St. Louis for one-on-one coaching visits with the administrators— back past empty storefronts and disintegrating homes to the clean, modern exteriors of the schools. The façade is just that—a veneer built by an embarrassed state spending money in response to harsh criticism in the early 1990s.

In this way, Jones is teacher and guide, helping the school system rebuild itself from the

inside out.

“It’s only hopeless when you look at the statistics and not into the eyes of the kids.”

—Dr. Christopher Jones, associate professor of education

“The grant provides the support system for principals not only to gain expertise but also to focus on the best way to positively affect student achievement,” said Denean Vaughn, director of curriculum and grants for the East St. Louis school district, and project director for this initiative. “Chris and the JP team are helping our current and future administrators approach problems from a whole new angle—being proactive instead of reactive.”

It was in 1991 that author Jonathan Kozol published his seminal and shocking account of the state of East St. Louis schools in the book Savage Inequalities. “There is, in fact, no exit for these children,” he wrote in summation, after detailing crumbling facilities and the inadequate curriculum taught within. “East St. Louis will likely be left just as it is for a good many years to come, an ugly metaphor of filth and overspill and chemical effusions, a place for blacks to live and die within, a place for other people to avoid when they are heading for St. Louis.”

In some ways, Kozol was right.

While the outside of the buildings has been fixed, the interior has deteriorated. By 2012, the school system—for many, the only opportunity for a decent salary—was so overrun with corruption, nepotism and abysmal test performance that the Illinois State Board of Education ousted the entire school board. With the school board and the state locked in a court battle since then, teacher pay and the future of the school system and its 6,300 students are in limbo.

Students pose for a photo at Annette Harris Officer Elementary School.

It’s the students who suffer. Even in 2013, nearly 25 years after Kozol alerted the nation to the plight of East St. Louis schoolchildren, only 18 percent of students passed their annual standardized tests.

“That’s why turning around these schools is so critical,” said Jones. “And the approach that we’re working on is teaching school administrators how to better deal with problems when they arise and how to set the tone so everything they do is working toward one goal: a better school for these children.”

Vaughn compares it to the teach-a-man-to-fish metaphor. “Chris is helping them develop skills so that when they are faced with a problem, whatever decision they make will be within the framework of everything else they are doing,” she said. “That leads them to the outcome they are looking for instead of shooting in the dark.”

But Jones doesn’t sugarcoat the effort it’s going to take. The onus is on the administrators, teachers, parents, community members and students to improve their own situation. But at the center of all that work: education.

“If you want to change a community, you have to start with the schools,” he said. “That’s the only way to effect permanent change.”

“The culture of the school was the pits.” Tina Frye, Officer Elementary School principal, recalls walking into the building on her first day two years ago and immediately feeling the tension. Her former school, Alta Sita Elementary, had closed, and the schools were merging staffs. “They were immediately disgruntled and full of distrust—of me, of each other, of everything. It was a toxic environment to be in.”

But Frye recalled one of the lessons that Jones had been repeating for the last four years: the sphere of influence.

The sphere of influence is a straightforward philosophy of management: be in control of what you can control—whatever is in your sphere—and don’t waste time on things you can’t change. It’s the kind of advice a grandmother might offer, but trying to put it into practice is harder than it seems.

“I stepped back and looked more at the big picture. I realized that I couldn’t solve a lot of the problems these teachers were having, so I had to refocus on what I could control.”

—Tina Frye, Principal, Officer Elementary School

The environment that greeted Frye when she walked in on day one is not uncommon in the East St. Louis school district. “When we got there, every one of the principals was running around all day putting out fires,” said Jones. They were exhausted and frustrated and didn’t have any time to step back and look at the big picture.”

Part of the issue was trust.

Administrators—knowing they were saddled with turning a failing school around—didn’t empower teachers to make any decisions. Teachers—frustrated by endless curriculum changes and overhauled administrative staffs—weren’t certain that whatever effort they put into teaching would be relevant in two years. State officials—not content to allow bleak test scores to worsen—demanded quick results.

Working within the sphere of influence concept, Jones and JP Associates developed

the “IFSAM” model of problem solving for administrators.

A four-step model, IFSAM focuses administrators’ efforts on data collection—the more data at their fingertips, the better administrators can judge what works. First identify the problem, then determine the function: why someone chose to act a certain way. Next, implement a solution and monitor the outcome. The goal is to make everything data-driven,” said Jones. “They need to find out what works so effective action can take place quickly.”

Each month, East St. Louis administrators present Jones with their IFSAM successes and failures.

For Frye, part of the solution was empowerment. “I made very specific choices, based on controlling what I could control, that helped bring the staff together fairly quickly,” she said. We established team leaders for each grade level—some from the current staff, and some from the staff coming in—and gave them responsibilities. Most of the teachers’ problems in the school were ironed out that way, without my involvement. But it was the IFSAM model that gave me the framework and confidence to find that solution.”

Frye’s story illustrates Jones’ vision for administrators in East St. Louis: leaders of leaders, not leaders of followers. “Obviously, if the building’s on fire, everyone needs to listen to one person and get out,” said Jones. “But for less immediate crises, empowering certain teachers to take some responsibility gives a principal the breathing room to step back and think about broad tasks, like turning around

an entire school.”

East St. Louis school administrators are learning to employ a four-step model that focuses on collecting data and making decisions based on that information.

The groundwork laid, collecting data on solutions is imperative. “You can have as many theories as you want to have, but until you get into a school and apply your theories to a specific problem, you don’t know if they work,” said Doug Blancero, a vice president at JP Associates who works closely with Jones. “We have had to be flexible in our beliefs in order to effect the best change in these school systems.”

Everyone who’s honest about East St. Louis’s plight admits it’s always been a gritty place and that it’s going to stay that way for awhile. At the turn of the century, it was one of the largest railroad centers in the country, with hardscrabble workers laboring in the livestock, aluminum, steel and paint industries.

But at the core has always been a struggle with race. Frustrations of striking white workers in the late 1910s over an influx of black workers fueled race riots. By the 1930s, businesses had started to leave and the race-based strife had led to major population losses in the city. The need for manufacturing during World War II led to a mini-resurgence, but whatever gains the city made were erased by the 1960s, and a steady decline has marked the city ever since.

This is a place where children bounce balls on cracked concrete slabs in the shadow of giant pollution-spewing factories to the north and south—a place Jones returns to month after month to chip away as much as he can of the old problems that plague the city.

“We aren’t studying something in a petri dish,” said Jones. “We are partners with the administrators, trying our best to use our knowledge and expertise to help them turn around this school system. We are there, and we are invested—it’s a ground-up approach.”

The sorest subject is test scores. Perpetually testing at or near the bottom of all Illinois schools, the scores have to begin to rise.

In 2013, only 18 percent of students passed their standardized tests, compared with nearly 60 percent statewide.

Like it or not, test scores are the bottom line measure of success for his efforts, and Jones becomes quietly serious when they are mentioned. “Everyone is concerned,” he said.

There are no more excuses—time has run out on that. We have to get these test scores up—the survival of the students depends on that. There are plenty of things working against these teachers, students, parents and school administrators, but they simply have to rise above them. There’s no other option.” It’s that urgency that keeps Jones coming back, month after month, year after year.

“These kids deserve better,” he said. “They deserve so much better. And we have to make

a better world for them.”