Yearlong discussion focuses on humanities and their impact on life

What does it mean to be a human? To be a member of society, contributing to the human experience? It’s nearly impossible to talk about without waxing poetic, or even cosmic, yet it’s a concept hard to pin down.

What does it mean to be a human? To be a member of society, contributing to the human experience? It’s nearly impossible to talk about without waxing poetic, or even cosmic, yet it’s a concept hard to pin down.

Our nation’s colleges and universities, which are charged with preparing young people for their adult lives, find themselves struggling with a central question as the emphasis on career preparation has grown in recent years. Is it, in fact, the responsibility of an institution of higher education to develop the whole student—that is, to act in a larger role than simply to prepare students for careers?

At Longwood, the site of the 2014 Virginia Humanities Conference on March 21-22, the conversation is ongoing. Leading up to the conference, Longwood organized a series of monthly panel discussions, each focusing on an aspect of the humanities.

“We wanted to build up to the conference in a way that stressed the impact each area of the humanities contributes to life,” said Dr. David Magill, associate professor of English and one of the organizers of the discussions. “We brought together students, faculty and outside speakers to comment on why one discipline within the humanities matters to their lives.”

Below are some excerpts from those discussions.

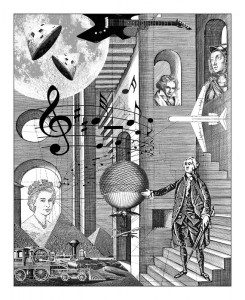

WHY MUSIC MATTERS

To what extent, then, does music provide a foundation for our experience of the world as a whole? Think about this for a minute. Everything in the world is in motion: pulsing, vibrating, producing rhythms. The ancients called this the “music of the spheres,” claiming that the movements of the celestial bodies generated a kind of cosmic symphony. They weren’t too far off. NASA’s Voyager has detected radiation emissions from planets in our own solar system. … The more you listen, the more you will hear the everyday music of a child beating on a drum, a trickling stream of water, a chorus of cicadas, the hum of traffic, a heartbeat. For me—as an avid consumer of music, student of the world and human being—music matters profoundly. It makes its own meaning and provides us with a different way of knowing and being in the world.

To what extent, then, does music provide a foundation for our experience of the world as a whole? Think about this for a minute. Everything in the world is in motion: pulsing, vibrating, producing rhythms. The ancients called this the “music of the spheres,” claiming that the movements of the celestial bodies generated a kind of cosmic symphony. They weren’t too far off. NASA’s Voyager has detected radiation emissions from planets in our own solar system. … The more you listen, the more you will hear the everyday music of a child beating on a drum, a trickling stream of water, a chorus of cicadas, the hum of traffic, a heartbeat. For me—as an avid consumer of music, student of the world and human being—music matters profoundly. It makes its own meaning and provides us with a different way of knowing and being in the world.

Dr. Kimberly J. Stern

Assistant professor of English

Music has its own vocabulary, syntax and structure. It is a physical activity, and, for professionals, muscle-brain coordination must be built in until music-making becomes instinctive and reflexive, able to adapt in any moment. Music is a unique way of knowing.

Large amounts of deliberate practice are even more important to eventual success as a musician than being a child prodigy. We are not only studying our field; we are learning our craft. Repetitive right practice builds success into the brain and into the body. Literally. Why is the study of music still relevant? Music breathes; it grows and changes because humans grow and change.

We know of societies without writing, and even without visual art—but none, it seems, lack music.

Specialists in other fields use music to learn more about the bodies they are trying to mend, cultures distant or long past, or the universe they are seeking to more fully understand.

Fifteen years ago, scientists dismissed the idea of trying to study musical emotion at all. But Tom Fritz’s 2009 study with the Mafa people of Cameroon demonstrated that perhaps musical emotion is also universal. Both Mafa and Western listeners reported similar emotional responses to music of both cultures, even though the music itself was unfamiliar.

Within the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to look at how our brains interact when we do music together. Music fosters social cohesion—it gets people’s brain states alive and even entrained together in time—so that we literally form communities larger than ourselves.

There is increasing recognition that music’s effect on the body, the brain and the emotions cannot be separated. Music is central to our very sense of self. Being musical is part of what it means to be human.

Dr. Pam McDermott

Assistant Professor of Music

WHY HISTORY MATTERS

History helps to explain the present and helps you to understand and appreciate the people around you. But it also gives you the capacity to cope with the future. I just want to mention a few ways in which it does this.

History teaches you that it’s not all about you. Like standing in west Texas, history makes you realize just how small you are in relation to the generations of people and civilizations who have come before you and will come after you if we play our cards right).

At the same time, history teaches you what a difference an individual life can make— and therefore should signal to you that your life is significant. And I’m not talking about being president or the first person on Mars— I’m talking about being someone like [Comanche chief and rancher] Quanah Parker or [Texas cattle farmer] Walter Ramsey. They were both men who valued kinship and community—and sought to preserve those values at all costs.

History teaches you to value both commonalities and differences. We can often see similarities between ourselves and those who came before us. But we also must reckon with the fact that the past is an entirely different place from the present. One historian has likened it to a foreign country: Words don’t have the same meaning, worldviews differ, and people dress and smell different. Trying to understand the past on its own terms—to look at it through the eyes of those who lived it—builds your own capacity to understand and tolerate those who are different from you.

And finally, and most importantly, history gives you a wider view. John Lewis Gaddis, a well-regarded historian of the Cold War, likens history to a landscape, and he sees the historian’s job to map it for us. As Gaddis explains, history is “the means by which a culture sees beyond the limits of its own senses. It’s the basis, across time, space and scale, for a wider view.” Like that landscape in west Texas, history gives you a wider view for miles around— a view beyond your own life into the lives of others and more broadly, into the human condition. Knowing history makes you a better human being.

Dr. Larissa Fergeson

Associate Professor of History

We must study history because it provides a valuable context for interpreting current events. How can you understand or appreciate the customs of a foreign country without knowing the reasoning behind them? How can you endeavor to solve a crisis without knowing why it exists in the first place? You simply cannot understand current events without understanding history. This is like reading the final chapter of a book without any knowledge of the rest of its contents. The fact that Snape kills Dumbledore means literally nothing to you—unless you know who Snape and Dumbledore are and what is happening around them. So, for instance, if you want to implement policies to foster peace in the Middle East, you must begin with studying the history of the conflict there.

Quite simply, history is what makes the world around us make sense. It is the how and why of who we are, where we are and what we are doing. Having a well-rounded knowledge of history, therefore, gives someone a very practical general knowledge of the world around them, which someone who lacks this sort of education simply does not have. People who have an education in history are better-prepared to connect with others from different backgrounds and to provide valuable insight on social and political affairs. These are the sorts of skills that make people suitable to be leaders in their communities.

Jaime Clift ’14

History Major

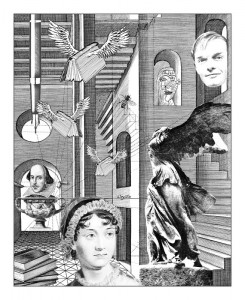

WHY LITERATURE MATTERS

To some degree or another, all academic ambitions are fueled by a desire to make sense of the world and to understand the human condition. Some disciplines achieve this by dissecting, categorizing, classifying or otherwise breaking the world into manageable pieces. Literature puts the pieces back together again. Wordsworth beat me to the punch in the Preface to his Lyrical Ballads: “If the labours of men of Science,” he writes, “should ever create any material revolution, direct or indirect, in our condition, and in the impressions we habitually receive, the Poet will sleep then no more than at present, but he will be ready to follow the steps of the Man of Science, not only in those general indirect effects, but he will be at his side, carrying sensation into the midst of the objects of the Science itself.” To put this less eloquently, literature is well-equipped and eager to take the work of science and put it back into the context of the world, and to bask in the awesomeness of the world, and to make it accessible. …

To some degree or another, all academic ambitions are fueled by a desire to make sense of the world and to understand the human condition. Some disciplines achieve this by dissecting, categorizing, classifying or otherwise breaking the world into manageable pieces. Literature puts the pieces back together again. Wordsworth beat me to the punch in the Preface to his Lyrical Ballads: “If the labours of men of Science,” he writes, “should ever create any material revolution, direct or indirect, in our condition, and in the impressions we habitually receive, the Poet will sleep then no more than at present, but he will be ready to follow the steps of the Man of Science, not only in those general indirect effects, but he will be at his side, carrying sensation into the midst of the objects of the Science itself.” To put this less eloquently, literature is well-equipped and eager to take the work of science and put it back into the context of the world, and to bask in the awesomeness of the world, and to make it accessible. …

When it comes up in conversation that I’m studying English, the first question is always, ‘Do you want to be a teacher?’ Since I go to Longwood it’s a fair question, but I most assuredly do not. At this point, I am left with a patronizing chuckle and, ‘good luck finding a job.’ The joke is on them. I have had one of the most important educations a young person can have in the 21st century. Reading, writing and critical thinking are skills that I will continue to develop and use regardless of how

I make a living. In a last-ditch attempt to connect all of the non-sequiturs: literature matters because it’s something humans do, and it’s something we’ve been doing for a long time. If we didn’t write, literature wouldn’t matter. If literature didn’t matter, we wouldn’t write.

Matt Jacobs ’13

English Major

In a word: Literature adds life to our lives.

Literature matters because it allows us to exercise our wonderful, maybe even divine gift of intimately experiencing words as symbols.

Literature compels us to think symbolically, to grasp symbols in powerful ways—windmills, a white whale, a sorcerer’s stone, an acorn that hit a little chicken on the head—and, for me, one of the most sinister and foreboding of all word-symbols, Pandemonium, the capital of Hell.

Literature matters because it not only compels us to think symbolically, it can enable us to act for the good of humanity. I strongly believe that literature helps all of us who are humane, moral and just be a hedge against inhumanity, immorality and injustice. I am thinking of that letter from Birmingham jail—and of course, all of the sacred texts of religions and the classics.

Literature matters because it can be life-defining. Literature helps us to create ourselves and, in turn, interpret ourselves—seemingly more than just “figuring out who we are.” Reading about the trials of Odysseus and his clever resolve to win them might just have helped some of us become who we are today—at least how we try to comport ourselves.

The experience of temptations that could most certainly yield disasters for us is not a new thing … and I think it helps to know this when we hear our sirens sing. Speaking of disaster, for me, one of the greatest sentences in all literature, “Has’t seen the white whale?” resonates in my self-concept. I can be obsessive and passionate and even self-destructive if I don’t watch it.

Literature matters because it can be, shall we say, sobering. Literature helps us grasp our mortality and maybe our immortality. If you have ever read or had read to you, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” you probably now understand individual and collective grief in a deep way that only a poem can cause. That poem was about Lincoln. I wonder how relevant it is for Kennedy. …

Literature matters because it is a powerful antidote to boredom. Boredom is what founding father of sociology Emile Durkheim called the monster of the cultivated mind.” The older I get and the more I observe our society, I think humans are more easily bored now than in the past. I can, with some effort, imagine living life without being a reader of literature, but it would be very, very boring.

In a word, literature adds life to our lives.

Dr. Ken Perkins

Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs

WHY ART MATTERS

Without art, we’d have nothing.

There would be no records of ancient Greek sculptures and frescos. There would be no evidence of us improving. Think about it. Without art, we wouldn’t even have this very building we’re in now. We need art in order to advance society and ourselves. We need art in order to broaden our horizons. And lastly, we need art in order to stimulate all sections of our brain.

Cameron Burns ’16

Art Major

I grew up about 30 minutes from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. To this day

I think about two exhibitions I saw while in high school: the early modernist sculptures of Constantin Brâncuși and Workers by documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado. Seeing their work in high school excited my imagination to the possibilities of art, and later, photography, as a means of communication. Brâncuși’s elegant “Bird in Space” captures, almost perfectly, the idea or essence of flight. Weightless and graceful, the object seems to float and almost dissolves into the gallery.

Perhaps it was Salgado’s series that cemented both my desire to be a photographer and the power of a single image. Salgado was an economist for the World Bank whose job it was to report on matters of international crisis. Finding words and charts to be inadequate, he quickly turned to photography to convey

issues of global importance. … Photography is perhaps our universal language of expression and particularly well-suited to convey ideas. This medium allows viewers to look directly at a photographer’s observation and see something in a way words often struggle to do. …

A typical roll of film—I still teach photography using black-and-white film—has 36 exposures. In the age of endless digital storage and limitless uploads to Instagram or Facebook, being constrained to just 36 photographs is a challenge. Even more challenging, perhaps, is you’re lucky to get one, maybe two, good photographs from that roll. Think about that: 2 for 36. Thirty-four failures. And that’s OK. To learn from those fleeting successes is to be creative. To try, over and over, to reflect on those two gems on your contact sheet and then to go out and do it again teaches us that failing is a critically important part of the creative process—learning from failure, as you do from success. Heaps of sketch books, ill-formed pots or an empty canvas taunting you from across the studio teaches us to keep working, keep looking, keep practicing the act of observation in order to transform our ideas into a physical form.

Michael Mergen

Assistant Professor of Art