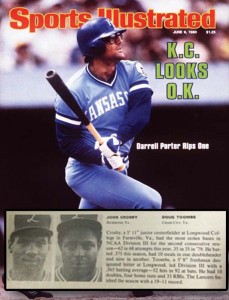

June 9, 1980, remains unforgettable for two former baseball players featured in Sports Illustrated

The mention of Longwood in Sports Illustrated’s ‘Faces in the Crowd’ feature brought attention to the fledgling baseball program.

BY ROHN BROWN ’84

In the summer of 1980, not many people outside Longwood College knew of John Crosby ’81 and Doug Toombs ’83. Competing as an NCAA Division III independent in rural Southside Virginia, Lancer baseball was unknown.

But a glimmer of the national spotlight shined on the baseball duo and the former all women’s college when Crosby and Toombs were featured in the June 9, 1980, edition of Sports Illustrated’s Faces In the Crowd.” Since 1956, “Faces” has featured the feats of amateur athletes. While a few such as Tiger Woods, Earvin Magic” Johnson and Bo Jackson become household names in the sports world, most do not.

The entry from 35 years ago reads as follows:

“Crosby, a 5’11” junior centerfielder at Longwood College in Farmville, Va., had the most stolen bases in NCAA Division III for the second consecutive season—62 in 68 attempts this year, 35 in 35 in ’79. He batted .375 this season, had 10 steals in one doubleheader and nine in another. Toombs, 5’8” designated hitter at Longwood, led Division III with a .565 batting average—52 hits in 92 at bats. He had 10 doubles, four home runs, and 33 RBIs. The Lancers finished the season with a 19-11 record.”

Crosby remembers former Longwood Sports Information Director Hoke Currie pointing out that he led the nation in stolen bases, but did not think much more about it.

Both men moved on from Longwood to pursue careers.

Crosby has been a teacher for 28 years, the last 18 with the Richmond City Public Schools. Toombs, who retired from UPS as a delivery driver, is now known as “The Hit Doctor” for his work as a hitting instructor in Chesterfield County and as the sponsor of seven youth baseball teams. Toombs is also is the head baseball coach for the American Legion Post 361 in west Richmond. Last year, Post 361 won the District 11 Championship and finished third in the state.

But the memory of their moment in the spotlight is still sweet. “To look in that book and see Chase City, Virginia, a very small town. It was amazing,” said Toombs. “There are a lot of my clients now who really don’t know who I am, and they go on the Internet and Google my name. I have customers come in here and say, Hey, you led the nation in hitting.’”

Former Head Coach Buddy Bolding, who had just finished his second season as the Longwood skipper in 1980, gives his players all the credit.

“All I did was put John Crosby in a place where he could steal bases, and I threw batting practice to those boys sufficiently to enable them to perform,” said Bolding. “And, of course, I put Doug Toombs in a place where he could best perform. If there is anything that I did, it was essentially to lower the reins on their mounts and let them run.”

Success on the diamond made the headlines. Their accomplishments behind the scenes tested their mental strength and perseverance.

Crosby found Longwood by accident. He completed his Associate of Science degree from Cumberland College in Tennessee and enrolled at Howard with aspirations of playing baseball. A coaching change prompted a look elsewhere.

The Richmond native and Armstrong High School graduate showed up at the registrar’s office at Virginia Union in January and ran into a former high-school friend, Jimmy Yarbrough ’82, M.S. ’96*. Yarbrough, who already transferred from Union, suggested Crosby join him at Longwood.

“I said, ‘Longwood, that’s an all-girls school,’” said Crosby, who is better-known as “Turk.”

“I’ll never forget it, this was a Wednesday. [Jimmy] said, ‘What if I could get you into Longwood, get you some financial aid and some money, and get you everything straight, would you be interested?’

“I said, ‘I’m not in school anyway, what the heck.’”

After a whirlwind campus tour of housing, financial aid and the registrar’s office, Crosby was ready to go. Classes had already started for the 1979 spring semester.

“The last thing we did was talk to Coach Bolding, and Jimmy introduced me. I will never forget that meeting,” said Crosby. “‘Coach, this guy’s a baseball player.’”

Bolding had already recruited a core of about 20 players from the Roanoke Valley and the Bedford County area for the 1979 season, his first at Longwood. Crosby was just one of a dozen walk-ons seeking a roster spot, said Bolding.

Crosby recalls, “Coach said, ‘We’ll give him a look-see. I pretty much have all my baseball players I need and have everything I want.’ He sort of blew me off, sort of said, ‘Whatever. We’ll give you a shot.’”

Crosby made the team, but that was only the first hurdle.

Growing up in the Church Hill neighborhood of Richmond, he was in a foreign environment and felt alone on the team.

“I was the only black guy on the team,” Crosby said. “There was no racism, nothing like that. Nobody disrespected me. They had their own cliques and were from the same hometown, the Roanoke area, which I understood.”

Crosby remembers not playing at the beginning of the season and growing frustrated.

Graduating fifth in his high-school class and a strong student at Longwood, he considered dropping baseball and concentrating on academics.

Again, Yarbrough provided timely advice.

“I would talk to Jimmy after the games and said, ‘I’m quitting.’ He talked me out of it. He would tell me to give it a few games and see how it goes.”

The hard work and perseverance paid off when Crosby earned a spot in the starting lineup.

“I did real well in those first couple games, got some hits, stole some bases, made some good defensive plays. The rest is history. [Bolding] came to me and said, ‘You’re going to be my lead-off batter and my centerfielder from now on.’”

Bolding, who expected his players to wait their turn for playing time, rewarded Crosby for his leadership and talents by naming him captain for two seasons.

“I just think I had to win his approval,” said Crosby. “He knew his kids. He knew what he wanted. I was a newcomer trying to fit into a system. Once I did, it was OK. “

The situation with his teammates was OK, too, Crosby said.

“I had my friends. I had my frat brothers. I had my cliques. Those are the guys I hung out with,” he said. “When it was baseball, we were cool; we were fine.”

Outfielder Bruce Morgan, who batted behind Crosby during part of his Longwood career, became a good friend at Longwood and now lives three doors down from Crosby and his family in Hanover County.

“John had a tremendous intelligence of what the pitchers’ intentions were,” said Bolding.

Crosby, like 95 percent of Bolding’s players, had the green light to steal, and he would go on any count, according to his former coach. Bolding credits another former Lancer, Jim Thacker, for helping give Crosby “the perfect storm of opportunity.”

Thacker, who also batted behind Crosby at Longwood, favored a closed stance and took a lot of low strikes that would have been ground outs. These low strikes were also harder for the catcher to handle and to throw out the stealing Crosby.

Bolding noted that Crosby is the only player he ever coached and the only player he personally ever saw who would occasionally steal second base without sliding just “for the fun of it.”

Crosby finished his three-year Longwood career in 1981 with 146 stolen bases and batted .303, .375 and .298. His speed was a game changer.

“If anything was hit in the outfield from center to the gaps, you could forget about it,” said teammate Toombs. “It was going to be caught. “

“I’ve never seen a guy who could run the way that he could. I’ve played a lot of ball and coached a lot of kids. His first step was just like, ‘Where did that come from?”

Crosby, who would also steal home on a dare, was his own boss on the base paths.

“[Coach Bolding] allowed me the freedom to hit and the freedom to run,” said Crosby. “I think if he was the kind of coach that held me back and said don’t steal until I give you the steal sign, then my entire career would have been different. But he gave me the green light, and he trusted me.”

Nicknamed the “Surgeon of Steal,” Crosby would don a pair of white batting gloves when he reached first base to match his white wristbands.

Crosby’s speed drew the attention of major league scouts, but he was never drafted or signed. Some say his arm was not major league ready.

He accomplished his primary goal, a B.S. in business administration in 1981. He later completed his master’s degree and teaching certification as suggested by Dr. Edna Allen-Bledsoe, a mentor and former Longwood faculty member.

Looking back, perhaps the “Surgeon’s” career was supposed to end at Longwood.

“My wife [Glennis] says that if I played baseball, we would have never met and we wouldn’t have these three great kids,” said Crosby.

The youngest child helped Toombs and Crosby reconnect. Brandon Crosby, a graduating senior at Atlee High School, took lessons from Toombs.

“He [Brandon] will be a better hitter than his father,” said Toombs. “He is on the right path, and Turk is the man to push him. Turk has been where he wants to go.”

Doug Toombs made his mark as a freshman, leading the nation in hitting and earning Division III All-American in 1980. Bolding believes that his record .565 batting average probably could not be achieved today. Toombs had 52 hits with only 92 at bats in 29 games.

Today’s Lancers play more games (55 in 2014) and there are no scheduled seven-inning double-headers. In 2014, four Lancers posted 200 or more at bats. Matt Dickinson led the team with 227.

“The point is that Doug hit .565,” said Bolding.

“Would he have hit .565 if he had 150 at bats? Probably not. It would have been substantially less than that. He played in the market that he was in, and you certainly can’t find fault over something that he had no control of and I had no control of.”

Without a tragic event, Toombs may have never been a Lancer.

In his senior year at Bluestone High School in Mecklenburg County, he was accepted at Virginia Tech and planned to walk-on the baseball team.

A week before the season started, his father, Albert Toombs, came to the practice field with bad news.

“Nine days before my 18th birthday, my mom passed away of a brain aneurism. That changed my [plans] on where I was going to school. Being an only child, it was just my dad and I. [I] wanted that opportunity for him to be able to see me play.”

Toombs dedicated his baseball career to his late mother, Ollie Jean Toombs.

Longwood, only 45 minutes north of Chase City, was a logical fit, and Bolding knew Toombs. The coach pitched for Keysville, and Toombs caught for Chase City in an adult league. Toombs also caught Bolding in an all-star game.

“He was not a power hitter. He was not a big guy. He only ended up hitting 11 college home runs, but he had a lot of line drives,” said Bolding. “[Doug was] a great line-drive hitter and could bunt his way on. He was a real fine hitter and understood the process of hitting very well.”

Mickey Roberts from district rival Nottoway High School also recommended him to Bolding, according to Toombs.

Toombs spent his first season as the Lancer’s designated hitter. It gave the freshman a chance to study college pitchers’ tendencies from the dugout.

“At any level, all pitchers have different slots that throw different pitches. All pitchers throw different pitches in different counts.”

His study of the pitchers and excellent hand eye coordination helped him as a hitter. Toombs boasted a .397 career batting average at Longwood.

His work behind the plate made him a complete player.

Bolding believes catchers should call the game behind the plate. Catchers with the right skill set make better decisions than the coach from the dugout, he said.

“To this day, Doug calls one of the best games of all the catchers I’ve had, “said Bolding. “He had the intelligence. He was not just good; he was an outstanding pitch caller.”

Bolding also rewarded Toombs for his hard work and leadership by naming him a captain his senior year.

Toombs recalled earning the respect of Lancer hurler and teammate Mickey Roberts in a game vs. Virginia Tech.

With a 0-2 count, Toombs called for a breaking ball inside. Roberts shook him off.

“So I go out to the mound and said, ‘Mickey, what’s going on,’” recalled Toombs. “He said, ‘I am going to strike this guy out.’ I said OK and go the plate and don’t even put down the sign. He throws a fastball right down the middle of the plate, and Franklin Stubbs hits it about 480 feet. I go out to the mound, and we have another conversation. I say, ‘See what happens when you don’t listen to your catcher?’”

Stubbs would later enjoy a 10-year major league career.

As a hitter, Toombs wasted no time in attacking the ball. About 80 percent of his hits were first-pitch fastballs.

“I was a patient hitter and looked for a mistake. When he made that mistake, I would make the pitcher pay for it.”

Toombs worked hard to excel at the game he loved..

“I used to cry when my mom said it was time to come inside. These kids [today] cry when their parents say to go outside. “

He remains very close to his father—the man who gave Toombs the opportunity to play baseball as a 10-year-old. Toombs was the first African-American child to play in the Chase City Community Park Dixie Youth League in 1971.

“My dad said that this is a community park and taxpayers’ dollars pay for the upkeep of this field and my kid is going to play,” said Toombs. “I broke the color barrier. People used to call me the ‘Jackie Robinson of Chase City.’ I didn’t want to disappoint him. He was opening this huge door for me. Now, I’ve had to go down there and show them I belonged. I think his doing that at such an early age helped to make me a better baseball player.”

Toombs’ challenges of growing up in Chase City as an African-American prepared him for a similar environment in Farmville.

“It was tough. It was more the off-campus life than on campus.”

“For me, I was from the country. I had listened to the stories from my father, who was actually born in 1941, and what he had physically seen. [He saw] the crosses burned in his front yard. I think coming from the town I came from helped me to understand what was happening in Farmville because the exact same thing was happening in Chase City.”

Bolding remembers the racial slurs directed at Toombs when the Lancers advanced to the regional playoffs in Valdosta, Ga., in 1982. He proudly recounts how the team supported and rallied around Toombs and won the South Atlantic Regional Tournament. They advanced to the Division II College World Series, another first for Bolding’s young program.

“I see the ‘82 season as a bunch of guys who were hungry,” Toombs recalled.

What may have been Toombs’ biggest accomplishment at Longwood came in 2010.

When he originally left Farmville in May 1983, he completed all the course work for his B.S. in social work. He simply could not pass the swimming proficiency test, a long-time graduation requirement.

According to the Office of the Registrar at Longwood, the last class of freshmen required to pass the swimming test entered Longwood in 1996.

Doug never had the opportunity to swim, much less take lessons as a youngster.

Bolding went to bat for Doug again.

“For years, coach Bolding fought this. He started fighting it in 1996, when they did away with the swimming requirement to graduate.”

“In 2010, he called me. ‘Doug, I’ve finally done it. You are going to receive your diploma. The only thing I ask is you walk with the 2010 class.’ I ordered my cap and gown and walked across to receive my diploma. Someone on the Board [of Visitors] was there when I was at Longwood initially. As I walked across the stage, they stood up right in front of me and said, ‘This is a proud day in this university.’”

Again, Bolding deflects the credit, giving it instead to Athletics Director Troy Austin and two other administrators at the time: Dr. Wayne McWee, then chief academic officer, and then President Patti Cormier.

“It was not something that I had to get in front of a jury and draw a long case because, at the end of the day, the people of Longwood care a lot about seeing individuals make the most out of themselves,” said Austin. Toombs’ academic record was reviewed by McWee and a faculty committee, who agreed that the swimming requirement should not prevent him from graduating, and the degree was granted.

That degree has come in handy for Toombs as a teacher on the diamond. He has coached recreation, high-school and American Legion baseball since 2000.

“I think the social work part of it has prepared me for what I do now,” Toombs said. “I see about 115 kids a week now, and, in my hitting business, no two kids are alike. I have to deal with this kid this way and that kid that way.”

And his students better be serious about their homework.

“All my students have work to do outside of here with me. If they don’t do it, then I don’t see them anymore. Once they walk through my front door and become students of the “Hit Doctor,” they are a reflection of me out on the baseball field. And I get my business on what I put out on the street.”

While he was never known as a power hitter, Toombs celebrates his students’ home runs. In his indoor batting cage in Chesterfield County, he shows them off in a display right next to an old aluminum bat that reads “NCAA Batting Champion .565.” This is the same bat he used as a freshman at Longwood to earn the national batting title.

The old bat is a reminder of where he came from and the people who influenced his life.

“Whatever you do in life, try to be the best at it. I think Coach Bolding tried to instill that in all his players. If you talk to all his former players that are coaching now, there are two things everybody will tell you about us. The biggest thing that everybody says about any player who now coaches and played for Coach Bolding is this: ‘They are very disciplined; they instill discipline in their players. They instill hard work in their players.’”

The “Surgeon of Steal” and the “Hit Doctor” were not just two pretty “Faces” in a magazine. They were pioneers as students, baseball players and African-American men. The Longwood community and the greater Southside Virginia area should be proud of their practice on and off of the baseball field.—Rohn Brown ’84

Rohn Brown ’84 is a free-lance writer and a sports enthusiast. He graduated from Longwood with a B.S. in business administration and earned a M.Ed. from the University of Virginia. He lives in Mechanicsville.

*Jimmy Yarbrough played basketball for the Lancers for two years (1976-77 and 1977-78) and still holds the single-game scoring record: 46 points. He would later would inspire students from disadvantaged households as the senior associate director of admissions. He died in 2005 after battling non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Jimmy Yarbrough Inspiration Award is now given each year to a student-athlete who exhibits exemplary performance academically, in intercollegiate competition and in community service.