Alumna’s new book reveals the stories of African-American physicians who volunteered to serve in World War I

Joann Buckley ’66 is the co-author of African American Doctors of WorldWar I:The Lives of 104 Volunteers, which was featured in February in a special Black History Month section in USA Today.

An illiterate boy who went on to earn a medical degree and become the first African-American to run a Veterans Administration hospital. Fredericksburg’s first African-American physician since Reconstruction. A physician who opened a hospital for the poor after he was denied “privileges” at a white hospital.

These are just a few of the heart-warming and heart-wrenching stories that have come to light in African American Doctors of World War I: The Lives of 104 Volunteers, a new book co-written by Longwood alumna Joann Buckley ’66 and Douglas Fisher.

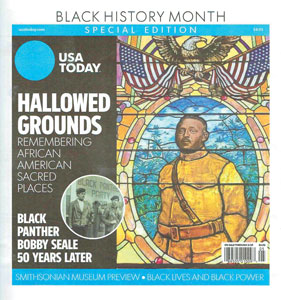

Released in December 2015, the book and the story of how it came to be were featured on the cover of a special Black History Month section of USA Today, and that’s only one example of the widespread media attention the book has garnered and the impact it will have.

“It’s a whole new field of study, and I think these biographies are only introductions. There’s a great deal more to be discovered by historians and graduate students writing dissertations,” said Buckley. “Many of these men are role models, and I would like to see their stories taught as part of American history in our schools.”

The stories are compelling, to say the least.

The first African-American to run a Veterans Administration hospital, for example, was the son of a former slave from North Carolina. At age 12, Joseph Ward, who was illiterate at the time, got a job caring for horses. His employer, a physician, took a special interest in the young boy, helping him get an education and eventually allowing Ward to train at his own homeopathic hospital. Ward then opened his own practice and continued his medical training until he received his medical degree at the age of 30.

In 1917, at the age of 44, he answered the call and volunteered for military duty during World War I. “This is a history- making period, and I want to be part of it,” was Ward’s simple explanation for deciding to risk his life for his country.

He rose through the ranks, eventually making lieutenant colonel. After the war, he went on to head the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center in Alabama.

Buckley and Fisher began work on the book after Fisher discovered letters and a diary written by his grandfather, a white supply officer for the U.S. Army’s segregated 92nd Infantry Division. Buckley, a former teacher who majored in history and English at Longwood, knew a good story when she heard one.

In 2009, she and Fisher began the search for the names of all the doctors who were a part of the Medical Officers Training Camp at Fort Des Moines. The list was finally found in an old decaying file at the National Archives. It included the hometowns, medical schools and ages of each of the 104 physicians. The couple then began gathering the details to bring each physician’s story to life. They searched through files at the Library of Congress, sifted through family trees, contacted families and local museums, and uncovered medical school and military records. It would take the couple five years to compile material for all of the biographies, including information about physicians’ service in World War I.

The image on the cover of the special section is a portrait of Dr. Urbane Bass, who was Fredericksburg’s first African-American physician since Reconstruction and the only one of the physicians

profiled in the book to be killed in battle.

Dr. Urbane Bass was the only one of the physicians to be killed in battle. Before he volunteered, he was Fredericksburg’s first African-American physician since Reconstruction. He opened a practice and a pharmacy before the war. A first lieutenant serving in France, he was frantically tending to wounded soldiers on the front line when a shell exploded nearby and claimed his life. Bass became the first African- American commissioned officer to be buried in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery on what is known as Officers Row.

There was also Dr. Dana O. Baldwin, who opened the first African-American medical practice in Martinsville. Returning home after the war, he was denied privileges at a white hospital. Baldwin ultimately opened his own 29-bed facility to mostly serve the poor. He named it St. Mary’s, after his mother.

If it weren’t for a chance meeting in an elevator, the stories of these inspirational men might have remained unknown, their service unappreciated.

“About three years ago, we met Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. in an elevator and started telling him about our research,” said Buckley, referring to the editor of African American National Biography, a series of volumes produced by Harvard University and Oxford University Press. “He immediately signed us to write 15 biographies.”

The combination of the good stories they were finding and the then-approaching centennial of the start of World War I gave Buckley and Fisher the notion that they had something special. They decided to approach McFarland & Company Inc., a publisher specializing in academic and nonfiction books based in North Carolina.

“Originally we never thought we were going to do a book, but people encouraged us,” said Buckley. When we reached out to McFarland, they got back to us in 90 minutes with a deal. In our careers, we have never done anything as easy as getting this book published.”

That appears to have been a very good decision by McFarland. African American Doctors of World War I went into a second printing less than a month after being released and continues to gain attention and positive reviews.

Buckley and Fisher have been interviewed on national podcasts and regional television across the country, and the authors were included in the Association for the Study of African American Life and History at its 2016 annual Featured Authors event in Washington, D.C.

The authors are scheduled at book signings and speaking engagements from Iowa to Maryland for the next several months, including an April 29 stop at the Moton Museum in Farmville that coincides with Buckley’s return to Longwood for her 50th reunion.

“When I think about it, Longwood gave me confidence in my abilities,” said Buckley. “They taught us to speak to people and smile at people as you walk across campus, and to never be afraid to try something new.”

Buckley took the lesson to heart. After working as a teacher in Virginia and Ohio, she studied graduate-level history and statistics. Then, in the 1980s, she moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a writer and editor. Her work with the National Newspaper Association included setting up and taking newspaper editors on international study missions.

“We were in Berlin and East Germany when the wall was coming down; in Poland during the Solidarity elections; in Czechoslovakia during the Velvet Revolution; in Leningrad during Glasnost; in Brazil for the First Conference on the Rainforest; and in Panama just after Noriega was taken out,” said Buckley. “It was very exciting.”

When asked about her constant pursuit of new and different experiences, Buckley’s answer is simple.

“I have no fear. If there is something I want to do, I just try it,” she said. “I’m in my 70s and have written my first book, so that should tell people a lot.”

Despite the attention and early sales success, for Buckley, the best aspect of the experience of writing African American Doctors of World War I has been meeting the families of the subjects.

“We have gotten to know so many of the family members of these doctors,” said Buckley. “And in many cases they didn’t know about their family members’ roles in the war. We were able to share with them part of the story, and they were able to tell us what happened after the war.”