Imaginative new master plan provides a framework for Longwood’s next chapter

BY MATTHEW MCWILLIAMS

A goal without a plan is just a wish.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

A new landscaped entry at the north end of Brock Commons will give visitors a sense of arrival and provide an ‘iconic photo moment.’

As Hannah Bailey walked across the graduation stage in front of Wheeler Hall on a sunny, unseasonably hot day last May, she looked out over the sea of visitors and thought of the future stretching out before her. Of course, she couldn’t know precisely how it would all unfold, but one important thing her time at Longwood had given her was a road map—a plan that reflected the kind of person she wanted to be, her goals and the things that would anchor her along the way.

Behind the graduates, tucked away beyond a row of maples, were construction fences encircling the site of Longwood’s new student center—a reminder of a campus that is busy with construction and renovation. Bailey’s four years at Longwood had seen a constant hum of progress on campus, with more in the pipeline. The fences reminded Bailey of how far she herself had come—and that she was also a work in progress.

Over the last two years, Longwood has been drawing its own roadmap—a master plan to set out a vision for the campus for the next decade and beyond. The plan is unusual, and, at the outset, its distinctive marching orders made it an irresistible challenge for one of the nation’s leading architecture and planning firms.

To be sure, the new “Place Matters” 2025 Master Plan envisions some new and important structures, including a performing arts center. But its principal focus is less about buildings than “place making.”

It starts with the premise of building on strength—driving the plan is a respect for the classical architecture that defines the heart of campus. And the unifying principle will be “new urbanism”—a design philosophy that values walkability, community interaction and free flow of energy. The idea is to make stronger all the elements that give Longwood and Farmville their rich sense of place and to enhance all the elements of a campus that help a community thrive.

President W. Taylor Reveley IV calls the Longwood campus one of the most profoundly important places I’ve ever been. It is at the crossroads of history and has developed a rich personality all its own. Our students are citizen leaders in the true sense of the word: active members of their own communities who take pride in working to make the world a better place. And, almost to a person, they say that commitment started because of Longwood.”

Preparation and Process

Campuses and large organizations across the country develop master plans for several important reasons: Constructing buildings uses valuable resources, and mistakes can be costly. Master plans provide the framework that ensures consistent, well-thought-out growth. On America’s handful of truly great campuses—a group in which Longwood certainly stakes a membership claim—the architecture and design are in harmony, and that takes concerted effort.

“The master plan is of paramount importance in the evolution of a university,” said Reveley. “It gives the campus the opportunity to reflect deeply on the direction in which we are headed and the priorities that make us unique, and to guide campus growth in that direction. Campus buildings have long life spans, so it’s important that we take the time to plan the right way. Longwood is growing, and haphazard growth is not a risk we are willing to take.”

John Kirk, a partner in the heralded urban planning firm Cooper Robertson, whose previous work included master plans for campuses such as Yale and the University of Pennsylvania, led 18 months of work to lay out the vision. The plan was truly built from the ground up: Planners conducted nearly 100 meetings with constituents on and off campus. They engaged in countless hours of detailed planning about everything from parking to wastewater, and led wide-ranging conversation about how the place of Longwood can reinforce the mission of cultivating citizen leaders.

“It takes a lot of thought to make an organically natural and flowing campus that is integrated into the community. We want people to be on campus and in town without noticing any separation …”

— PRESIDENT W. TAYLOR REVELEY IV

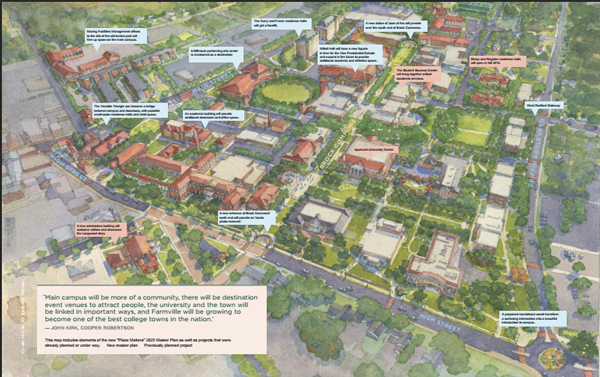

As the vision began to take shape, Kirk and his partners split the campus into three sections, or “precincts,” each with its own distinct characteristics and challenges: north campus, the historic core along High Street up through Wheeler Mall; central campus, with Brock Commons at its heart; and south campus, the athletics fields all the way to Moton Museum. Looking at these pieces individually, planners uncovered the unique opportunities within each and dreamed of ways to build on the best of Longwood.

“There is an extraordinary quality to the open spaces at the northern end of the main campus: north Brock Commons, Wheeler Mall and Beale Plaza,” said Kirk. “This is in stark contrast to the central and south ends of campus, where the outdoor rooms lose the character inherent in the northern portions of campus.” Kirk said the challenges in the central and southern parts of campus are due both to the architecture found there and to the less attractive landscaping. “An important aspect of the master plan was to extend what is so lovely at the northern end of the campus to the southern end,” he said.

Planning is the key to achieving these goals, said Reveley. It takes a lot of thought to make an organically natural and flowing campus that is integrated into the community. We want people to be on campus and in town without noticing any separation, moving back and forth with a sense of ease and familiarity,” he said. “That doesn’t happen without a lot of planning.”

The Presence of Past

To build on what makes Longwood special, planners had to first look backward. It was no mistake that interspersed among the renderings and architectural concepts at the December unveiling of the plan at the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts were pieces of Longwood’s past: a hinge from the original Ruffner building, a piece of one of the many French columns that adorn campus buildings, miniature replicas of Longwood’s Joan of Arc statues.

Longwood is one of the hundred oldest colleges and universities in the country, and, through the years, she and her students have been witness to and participants in some of the seminal moments of American history. From the Civil War to the civil rights movement, Longwood has been awash in events that shaped our country and knitted our nation together, and it is to time and history the university owes its unique perspective and rich culture.

So, what is this place called Longwood?

Longwood is Chi, the secret organization that has survived for more than a century as a guardian of the spirit of campus. Longwood is Ruffner Hall, its stone threshold worn down by millions of footsteps. Longwood is Donna Anuskiewicz, the Rotunda editor who published a blank editorial in the school newspaper in an act of courage and defiance to protest the closing of local schools. Longwood is nearly two centuries of citizen leaders who have left campus with a sense of purpose and being—many of them going straight into classrooms where they have taught generations of children.

Longwood is Farmville, indelibly linked to and reflecting the spirit of its hometown—the hub of a vast region that is home to a diverse community and rich in history and achievement.

As planners considered campus growth, the people and history of Longwood’s rich past served as inspiration and, in some cases, clear guidance on priorities. Kirk and his partners sought to create public areas where the Chi spirit can grow even stronger through vibrant interaction. They laid out that new buildings should be in harmony with the spirit and scale of Ruffner Hall. They celebrated our local history by creating distinct pathways to Moton Museum, bringing the triangle formed by Main Street, High Street and Griffin together in a seamless way.

Knitting Together Campus and Downtown

What emerged after the year planners spent poring over maps, photos and notes and talking with countless faculty, staff, students, alumni and community members were several opportunities to significantly impact the lives of future students and to extend the fabric of campus into downtown Farmville. The ultimate goal is to develop what they hope will become one of the great college towns in America.

Transformations: South Brock Commons

Art has long been a hallmark of Longwood, with two sculptures of Longwood’s patron hero, Joan of Arc, taking center stage. “Joanie on the Stonie” and “Joanie on the Pony,” as the two statues are affectionately known, may soon get some company. Renowned Scottish sculptor Alexander Stoddart—one of the most celebrated neoclassical sculptors today—is creating a monument of the 15th century heroine to stand at the southern terminus of Brock Commons. Instead of a sword, Joan will be holding her banner, which she is said to have favored over a weapon. The statues currently in residence on campus are an integral part of life at Longwood. Joanie on the Pony, a reduced version of the bronze masterpiece by Anna Hyatt Huntington that for many years resided in the Colonnades, is often credited with stopping the 2001 fire that destroyed Ruffner and Grainger halls from spreading. Joanie on the Stonie, by French sculptor Henri-Michel-Antoine Chapu, has been a source of good luck to generations of Longwood exam-takers. The sculpture is located beneath the iconic Rotunda in Ruffner Hall.

Art has long been a hallmark of Longwood, with two sculptures of Longwood’s patron hero, Joan of Arc, taking center stage. “Joanie on the Stonie” and “Joanie on the Pony,” as the two statues are affectionately known, may soon get some company. Renowned Scottish sculptor Alexander Stoddart—one of the most celebrated neoclassical sculptors today—is creating a monument of the 15th century heroine to stand at the southern terminus of Brock Commons. Instead of a sword, Joan will be holding her banner, which she is said to have favored over a weapon. The statues currently in residence on campus are an integral part of life at Longwood. Joanie on the Pony, a reduced version of the bronze masterpiece by Anna Hyatt Huntington that for many years resided in the Colonnades, is often credited with stopping the 2001 fire that destroyed Ruffner and Grainger halls from spreading. Joanie on the Stonie, by French sculptor Henri-Michel-Antoine Chapu, has been a source of good luck to generations of Longwood exam-takers. The sculpture is located beneath the iconic Rotunda in Ruffner Hall.

“Longwood’s physical connection to the community and the town of Farmville is tenuous and not as strong as it can and wants to be—a function of the street conditions and Venable Triangle (formed by Main, Venable and High streets),” said Kirk. “The Venable Triangle acts more like a wedge between town and campus, when it wants to be a bridge.

“Griffin Boulevard and South Main Street are too wide, which encourages motorists to drive too fast, making these streets the equivalent of rushing rivers that are too difficult to navigate. The master plan makes significant strides toward correcting these conditions so that the fabric of Longwood can be seamlessly knitted to that of the community and of the town.”

Seamlessness is a trademark of every great college town. Visitors to Charlottesville often can’t tell if they are actually on campus or on a street near U.Va., so seamless is the transition. The same effect is repeated across the country, from Austin to Ann Arbor. The increased commerce, the sense of pride and the abundant energy are all byproducts of the free flow of people from campus to town and back again.

That principle—a hallmark of the new urbanism philosophy that Cooper Robertson employs—was central to crafting every element of the master plan. From a proposed roundabout at the intersection of High Street and Griffin Boulevard that would turn a confusing intersection into a beautiful introduction to campus, to a performing arts center that will become a destination event venue and attract people from far and near, the heart of the master plan is its emphasis on creating public gathering spaces and community-minded growth.

“This master plan was different from every previous one I’ve worked on in one distinct way: Everyone was welcome,” said Richard Bratcher, a former vice president at Longwood who led the master plan effort. “There was a constant and open dialogue between the planning firm, stakeholders at Longwood and members of the community. Every idea was examined, and every concern considered. It was truly a community effort, and that’s reflected in the plan.”

Transformations: Willett Hall

The site of the 2016 U.S. Vice Presidential Debate, the Willett Hall façade will change dramatically in the coming months, with a bigger expansion planned in the future. Immediately, a new entrance will adorn the front of the gymnasium, echoing the French columns that grace many of campus’s iconic structures. The façade will serve as a handsome backdrop for news broadcasts as hundreds of cameras point in its direction to provide coverage of the debate in early October. Long-term plans call for an expansion of the building, dramatically increasing the academic space used by our thriving Health, Athletic Training and Kinesiology department. In addition, space will be carved out for a true Division I facility for Longwood’s men’s and women’s basketball teams. Such a large space has many other purposes, from indoor ceremonies to multiple class reunions. Planners identified a large multipurpose space as a pressing need for a growing campus, and a Willett Hall expansion puts that space at the heart of campus.

The proposed performing arts center sprang from one such conversation. Early in the process, planners were considering unfinished pieces from a previous master plan completed in 2008 and came across the arts center—a 500-seat venue that could be home to various concerts and performances. Captivated by the idea and understanding its potential impact on the community, planners shifted the location to Main Street, where it could nurture the best kind of community-campus engagement.

The most radical shift, however, is also one of the most exciting. When first-time visitors to campus crest the hill on south Main Street, they are presented with a view that is the polar opposite of the beauty and charm of north campus. Blocking what could be a beautiful tableau are the backs of the scoreboards at the athletics fields.

The master plan envisions new baseball and softball stadiums to be built along the High Bridge Trail, structures that would fit the community the way Camden Yards or PNC Park fits Baltimore and Pittsburgh—integral spaces that reflect a town’s character. The stadiums would be home to Longwood student- athletes and possibly a minor league team.

Hannah Bailey says she made it to High Bridge—one of the bucket-list experiences for any Longwood student— eventually. “To be honest, I didn’t really know how to get to the trail,” she said. “I found my way to the downtown crossing but didn’t realize where the bridge was or how to get all the way out there. When I saw the plans to put the baseball and softball stadiums along the trail near campus, I thought that students like me wouldn’t have that problem in the future.”

Transformations: Curry and Frazer

Iconic, if only for their looming presence, Curry and Frazer residence halls make a big impression in Farmville— but not always a positive one. Home to hundreds of freshmen each year, the halls are often remembered as large boxes lacking character. The master plan reimagines Curry and Frazer to reflect the look and feel of the rest of campus. Simple additions, including peaked roofs and different window treatments, coupled with landscaping improvements along Main Street, will give the high-rises and one of the entry points to downtown an attractive and welcoming new look.

Such a shift serves dual purposes. First, it further integrates the campus with the community. Second, it allows field sports to be consolidated at the southern triangle of campus and the opportunity to build a greenway all the way from High Street to Moton Museum, truly connecting the historic northern core with the rest of the university.

Enriching the Longwood experience for students like Bailey was also an important goal of the plan.

“As Longwood implements the design proposals embedded in the new master plan, along with those projects already in the pipeline, the student experience will improve progressively,” said Kirk. “Main campus will be more of a community, there will be destination event venues to attract people, the university and the town will be linked in important ways, and Farmville will be growing to become one of the best college towns in the nation.

“In short, Longwood and Farmville together will have more vibrancy and will become a repeat destination for alumni and non-alumni alike—all of which will enrich the student experience.”

A sense of promise and possibility inspired by the plan is pervasive among members of the Longwood/Farmville community, said Bratcher.

“This plan has been met with near-universal excitement, and that’s rare with these things,” he said. “One important aspect of our master plan is that it is achievable. We have the resources and mechanisms in place to see this plan through, and that’s exciting.”

Bailey, who stayed on at Longwood to work on a master’s degree and hopes to put her Longwood degrees to work in an elementary school classroom, sees new meaning in the construction fencing she’ll pass by again on the way to her second commencement ceremony in May.

“Change is inevitable and so is growth,” she said. “Just a glimpse of what campus is going to be for the next generation of Longwood students makes me excited to come back year after year and see how it’s grown. It will always be a second home for me.”

hover over images in the gallery for descriptions

A Place for All of Us

The Longwood Master Plan was officially unveiled on a cool December evening in 2015. Hundreds of people—community members, alumni, faculty and staff—gathered on the ground floor of the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts to hear from President Reveley and the architects. On display throughout the exhibit space were elements and artifacts of the plan and the planning process.

Standing among large sheets of tracing paper bearing outlines of campus and hand-scratched notes, Kirk recalled his first visit to campus, reminiscent of a freshman student on his first day. “I felt immediately an energy that isn’t present on other campuses—a camaraderie that you could almost touch,” he said. “I walked through these beautiful grounds amid these stately buildings, and an impromptu volleyball game broke out in front of me. I could tell right away this was a special place.”

That sense of place—a feeling shared by tens of thousands of alumni and everyone else who makes up the sprawling Longwood family—became the framework for the master plan.

“We always believe you start with the setting and go from there,” Kirk told the LCVA crowd. “Longwood has a lot of good bones to build on, and we worked from the premise of taking what is great about this place and building on it. It’s not that the campus will be radically different in 20 years. It will be the same—but better.”

In Kirk’s imagination and in his presentation, a moment that Hannah Bailey experienced as she stepped off the commencement stage last May loomed large.

“Think of the great campuses in this country,” he implored the crowd. “They all have an iconic photo moment— a place where students take photos when mom and dad drop them off on their first day on campus and then again four years later on graduation day. Just here in Virginia, there are the colonnades at U.Va., the Drillfield at Tech. Longwood is missing that iconic photo.”

The first major change will be the construction of a show-stopping semicircular brick gateway at the northern terminus of Brock Commons where it meets High Street. In the coming years, when Bailey returns to campus for alumni reunions or to visit friends and professors, she’ll walk through that gateway to a campus transformed. As Longwood evolves over the next decade, students just like her will enjoy a thriving university that is deeply linked to the surrounding community.

Click the image above to see a more detailed view of the upcoming changes.