What I Did On My Summer Vacation

Students and faculty spend eight weeks working side by side on research ranging from astrophysics to bird urbanization

On a warm, sunny, early Sunday morning in June, Dr. Sujan “Henk” Henkanaththegedara is looking up at the tall pine trees ringing a clearing at Pocahontas State Park in Chesterfield County, making strange whooshing sounds like wind with his mouth.

“I can hear a nuthatch,” the assistant professor of biology says. The noise does the trick—nearby birds come out from hiding, intrigued. From a distance, he spots an Eastern phoebe on a fence post exhibiting characteristic tail flicking. His research student, biology major Caryn Ross ’15, jots down a running list of the birds in her notebook.

“There are some birds, you can tell them just by the silhouette. Most of them by the call, if you have enough experience,” Henkanaththegedara says to the small group he’s leading. “I can hear a mourning dove,” he tells Ross. “I can hear a crow. There’s a Carolina wren—its call sounds like ‘tea kettle, tea kettle, tea kettle.’”

Henkanaththegedara, who is conducting a research study of the effects of urbanization on Virginia bird populations, is one of 11 professors who worked with 13 Longwood undergraduates on research projects this past summer through the university’s PRISM (Perspectives on Research In Science and Mathematics) program.

PRISM, which has now been offered two summers in a row, pairs professors with students to work full time together on significant research projects for eight weeks. Students who are accepted into the competitive program receive a stipend and room and board in addition to the unique opportunity to perform intensive research that may end up being published in academic journals and presented at conferences.

The PRISM projects promote STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) research in the fields of biology, neuroscience, environmental sciences, physics, psychology, chemistry and mathematics.

“I was an undergraduate in the mid- to late-’60s. When I was in grad school, the idea that you would participate in research before you were a Ph.D. student was just unheard of.

The idea that an undergraduate student could get his name on a paper was unheard of,” said Dr. Gary L. Page, a visiting assistant professor of physics whose daughter, Kelly Wolcott Kahn ’05, is a Longwood graduate.

“Longwood in particular takes great pride in the way it provides undergraduates with opportunities to engage in real, serious, scholarly activity,” said Page, who worked with a student researcher on an astrophysics PRISM project this summer.

Dr. Kathy M. DeBusk, an assistant professor of environmental science who also led a project last summer, said PRISM research exposes students to the field, what it entails, how you work with people, how you set up an experimental design and follow through with it to determine a conclusion.”

“It teaches a plethora of skills that can be applied to any career path they choose to take—communications skills, writing skills, teaching skills. We want to prepare our students for any career path they choose to take,” DeBusk said, “whether that be research, whether it be academia, whether it be private consulting. We want them to be prepared for any of those avenues.”

A few of the PRISM 2014 projects are described below.

Storm-water Management

DeBusk is partnering with Arlington County to study ways to increase citizen participation in the county’s StormwaterWise program to remediate storm-water management in residential areas.

Storm water rolling along concrete surfaces such as roads and parking lots can pick up hazardous substances such as oil, gasoline and fertilizers and carry the pollutants into lakes, streams and rivers. In the past, local governments tried to battle the problems with centralized drainage retention ponds, DeBusk said, but environmentalists are now advocating a decentralized approach such as Arlington’s program, which encourages citizens to take actions such as utilizing rain barrels, making landscaping changes or removing

concrete sidewalks.

The PRISM project conducted by Dr. Kathy M. DeBusk and Alyssa Robinson ’16 focused on increasing citizen participation in a residential storm-water management program.

DeBusk’s student research assistant, Alyssa Robinson ’16 of Midlothian, a double major in biology and integrated environmental sciences, worked on an electronic survey to deliver to hundreds of county residents. After collating the collected data, the pair wrote a report and presented Arlington with their findings, along with recommendations for improving the storm-water program.

DeBusk also plans to submit the results to journals and to present the findings at a conference in 2015 in hopes of helping other communities find solutions to storm-water management.

“She’s really great,” Robinson said of DeBusk in an interview this summer.

She has been more than helpful. She really lets me take ownership of everything I do. She’s had me write up all the survey questions. She’s really let me take the reins on this one.” She added, laughing, “It’s kind of

scary, really.”

Robinson hopes to be a professor herself one day and has enjoyed her first taste of the research side of academia.

“I was there in an advisory capacity,” DeBusk said. “She was doing the majority of this, with me providing assistance and guidance when needed. I think that’s the way you learn best and get a feel for what research is all about. She did what she could do, and then, when she hit a wall, we got together and brainstormed and figured out a way around it.”

Mind Over Dark Matter

On the outer reaches around our solar system, past Neptune’s orbit, lies the Kuiper Belt, a dense ring of asteroids and dwarf planets. It was theoretical for more than 60 years until it was discovered in 1992.

Similarly, for about 80 years, astrophysicists have noticed that the movements of some stars seem to be reacting to the gravity of some unseen mass. Scientists theorize this to be an unknown substance called dark matter, and they’ve been looking for it as far back as the 1930s, when astronomer Jan Oort first hypothesized its existence.

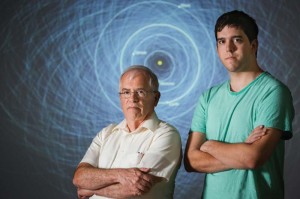

Dr. Gary Page (left) and Nick Carr ’15 examined the orbits of asteroids in the Kuiper Belt.

But what if there’s no such thing as dark matter? What if we just don’t know as much about how gravity works as we think?

That’s the question Professor Page and his student assistant worked to answer in their PRISM project this summer.

Page and his research assistant, Nick Carr ’15, a physics major from Roanoke, combed an astronomical database for several multiple observances of the same asteroids in the Kuiper Belt. They plan to examine the orbits to see if the objects behave as expected, given the present understanding of gravity and the

motion of the planets.

“I’ve been trying to narrow down searches for which asteroid we’ll be using, trying to figure out which one gives us our best shot at giving us the best data or the most observations to use,” said Carr in a mid-summer interview. “If I enjoy this like I think I will, I will try to get into grad school for astrophysics.”

Page said, “I think it’s fair to say that if we discovered evidence of either … an accumulation of dark matter in the outer solar system or that there was a discrepancy in the motion of small bodies in the Kuiper Belt, that would be a pretty major finding.”

Traumatic Brain Injury and Motherhood

For the past four years, Dr. Adam Franssen, assistant professor of biology, has been studying the neural enhancements enjoyed by mothers. During the PRISM research project he conducted during the summer of 2013, he and Alexandra Hauver ’14 found that mother rats are capable of using sophisticated decision-making methods to identify and care for their young. They presented their findings at the 2014 Society of Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Keaton Unroe ’17 worked with Dr. Adam Franssen to research ways of protecting the brain from traumatic injury.

Franssen’s theory is that motherhood confers chemical advantages in the brains of mammals. Now he’s trying to find out if those same advantages can be imparted through pre-emptive enrichment activities such as adding brain-stimulating toys and living in nicer environments.

“A lot of the traumatic brain injury work being done now is about enriching the environment of the victim after the injury,” Franssen said. “We’re taking a slightly different angle and asking what things you can do in the first place to protect your brain.”

Franssen’s student research assistants for the summer 2014 PRISM program were biology majors Keaton Unroe ’17 of Clifton Forge and Brian Lotts ’15 of Newport News, who plans to get his doctorate in physical therapy.

Lotts said the PRISM research required him to take on more responsibility than he expected, noting that the research team worked five days a week and then performed health checks on the rats during the weekends.

“It was a nice change from the classroom, where instead of learning science, you actually got to do science,” Lotts said. “In the classroom, you learn about already known discoveries, and we worked with something new.”

Inspired by the research, Lotts said he’s considering how he might apply his experience with behavioral neuroscience to physical therapy, helping victims of traumatic brain injuries.

The Secret to Fighting Bacterial Infections

Sarah Nuckolls ’15 (foreground) and Kelsey Trace ’15 studied more effective ways of fighting bacterial biofilms, which are usually what make people sick—not the bacteria themselves.

Surprisingly, it’s not usually bacteria that make people sick—it’s a biofilm that bacteria grow. “Roughly 80 percent of bacterial infections within the body are caused by bacterial biofilms,” said Dr. Andrew Yeagley, assistant professor of chemistry. “The main cause of getting sick is the formation of a biofilm

by bacteria.”

But the medical and pharmaceutical industries focus on killing the bacteria with antibiotics, he said, “and all that does is breed bacteria resistant to that antibiotic.”

This summer Yeagley and his student research assistants prepared small molecule antimicrobials based on a compound called isatin that plays a role in the formation of biofilms. They plan to test these small molecules on various strains of bacteria, including E. coli, to see if they can stop the bacteria from creating biofilms.

Yeagley’s student assistants are Sarah Nuckolls 15, a chemistry major from Fairfax, and Kelsey Trace ’15, a biology major from Gainesville.

“I wish I had minored in chemistry because I didn’t realize I would like it so much,” Trace said in a mid project interview. “It’s a lot of fun. It’s like a puzzle you have to figure out.

I love it. Chemistry is awesome, and everyone should do it! “A lot of the work we’re doing is stuff no one has ever done before so there’s no literature about it. A lot of it is trial and error and doing calculations and setting things up—trying to predict how things are going to happen. It’s been an experience that I feel is close to what I would get in the real world. Potentially this is something I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Still unsure whether she’ll go to grad school immediately after college or seek employment first, Trace eventually wants to conduct research that could help people like one of her close family friends who struggles with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. “I’d like to make a difference in his life and for patients like him,” she said. “Ideally, I’d like to contribute to a therapy or treatment.”

City Bird, Country Bird

A hawk gently glides high over a grassy field. Tracking the flight through his binoculars, Professor Henkanaththegedara opens the backpack slung over his shoulder and pulls out a copy of The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America, confirming that the predator is indeed an immature red-tailed hawk.

Far below the hawk, a vibrant Eastern bluebird swoops by as a pair of Canada geese loll among the tall green grass blades, still wet with early morning dew.

Caryn Ross ’15 and Dr. Sujan Henkanaththegedara put their binoculars to good use this summer observing birds.

“Sujan is a great teacher. It’s fun to go birding with him because he knows an awful lot of songs. He can pick them right out,” said fellow bird-watcher Warren Rofe. (Rofe is the father of Dr. Amorette R. Barber, an assistant professor of biology at Longwood.)

Henkanaththegedara has been birding since he was a boy of 13 in Sri Lanka. At his various academic assignments, he’s been bird-watching in locations as diverse as the Mojave Desert and North Dakota.

In his first year at Longwood, Henkan-aththegedara’s PRISM project is looking at the impact of urbanization on birds by comparing bird populations in urban areas such as Richmond and Petersburg with those in state parks such as Bear Creek Lake, Holliday Lake, James River and Pocahontas. Initially he’s finding that there are fewer species but larger numbers in the cities. Urban birds tend to be seed eaters; rural birds tend to live on insects.

By examining historical Audubon Christmas Bird Count data, Henkanaththegedara has also found a huge decrease in the number of Northern cardinals, Virginia’s state bird, over the last 50 years in the state’s Central Piedmont region. He’s not sure yet if it’s due to climate change, loss of habitat or increased use of pesticides. “That’s the beauty of ecological research—one finding will generate 10 new questions,” he said.

Among other possibilities, he said, his research could be used to promote green spaces in urban planning to increase the diversity of bird species.

“This is the first time I’ve ever done any kind of birding,” said his research assistant, Caryn Ross, of Charlottesville, daughter of Dr. Charles D. Ross, professor of physics. “I actually really like it, and I think I’m going to do something with bird conservation or wildlife conservation research in grad school.”

Dr. Melissa Rhoten, professor of chemistry and PRISM director, said giving students that kind of experience is just what Longwood had in mind when it developed the program.

“PRISM allows students to engage in high-level research as undergraduates with some of the university’s best faculty members,” she said. “These students are top candidates for admission to graduate and professional schools and for STEM jobs in Virginia and beyond.”